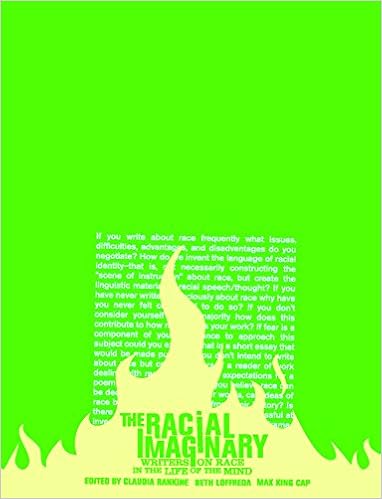

Who is permitted to write about Race and People of Color? Claudia Rankine is a renowned poet whose popularity seems to increase as her “prosecutorial” formulations multiply. Receiving several prestigious nominations and awards, Rankine is at her best when writing about the Universal or the Transcendent (“Some years there exists a wanting to escape.”), literary configurations that Rankine dismisses in the volume under review. The Introduction to The Racial Imaginary, written with the writer, Beth Loffreda (hereafter, R&L), informs us that Rankine initiated the Racial Imaginary project online with “an open letter about race and the creative imagination” (p 13), soliciting readers' responses. The resulting book presents 28 selected posts, illustrated by strong and timely artwork chosen by the artist Max King Cap.

R&L's Introduction is most emphatic when rejecting “the imagination [as] a free space” (15) and when arguing that “To say, as a white writer, that I have a right to write about whoever I want, including writing from the point of view of characters of color—that I have a right of access and that my artistry is harmed if I am told I cannot do so—is to make a mistake.” (15-16). These themes continually resonate with the reader. The volume is divided into five Sections—Institutions, Lives, Readings, Critiques, and Poetics. Institutions highlights R&L's distinction between Race and Racism, and a wide range of intensely personal, even, confessional, voices describe their experiences, mostly in the form of seemingly cathartic expressions of white guilt, realizing the Editors' prediction that, “[The 'internal tumult' will] be made up of some admixture of shame, guilt, loathing, opportunism, anxiety, irritation, dismissal, self-hatred, pain, hope, affection, and other even less nameable energies.” (21). The entries in the book's first two Sections, and their sometimes discomforting revelations, left me wondering about the power differentials and dynamics between Rankine and most of the other writers. The potential for Rankine's voice to influence, if not intimidate, her subordinates should be considered; although, Rankine might counter that attempts to construct a hierarchy based upon rank, prominence, or authority inherently reflects structural racism, classism, and sexism. Clearly, Rankine intended her Racial Imaginary project to be an egalitarian and communal effort.

The Section, Readings, begins with a well-researched and instructive essay by Joshua Weiner. He has a fundamentally progressive goal, “to disrupt the structure, so that we can see it” (124). Weiner's tools for dismantling power structures are ideas and words, and his cogent analysis of representations of identity in several texts privileges the universality of the theme, “the individual and society.”

Critique is a brief Section addressing the challenging topic, “writing race”. As a self-described “black woman”, Diane Exavier states, “I feel like race isn't something I always want (or need) to talk about, but it is something that other people won't let me forget.” (205). Importantly, this author proposes a solution: “I truly believe that it is the recognition of the Other that ultimately leads to unification.” (206). However, Exavier does not tell us how to do this. In the same Section, Soraya Membreno's perspectives on race and ethnicity are refreshing and unique in this volume. “I am Hispanic, yes, but that's not your business.” (212). And, later in her essay, “Race does not define me, it is my culture, but it is not me.” (213). Membreno asserts her right to define her own identity, a timely topic given recent debates about Rachel Dolezal's “passing” (also see Lacy M. Johnson;s piece in this section and Tamiko Beyer's essay on page 245).

The Poetics Section includes 15 brief entries on how individual poets engage the topic, “Race”, in their practices. I wish this Section had been expanded to include more personal reflections on the process of writing poetry. The book would have benefited from a discerning summary chapter written by R&L with the purpose of placing in perspective similar and different themes and trends across essays, including, a (revised) conceptual framework, particularly, since many of the contributors' views seem incompatible with those of the Editors as proffered in their Introduction.

A particularly evident, though, possibly, useful, consequence of reading each essay is thinking about the inherent inconsistencies of assumptions and intellectual constructs employed by the authors, and it might be worthwhile for scholars to “unpack” the subtexts and deep structures within and between Sections. Indeed, Rankine, herself, may have some ambivalence about her rejection of the Universal and the Transcendent, since the “voice” of her 2014 book, Citizen (Graywolf), employs many generic references and sentences relevant to all humans, especially, marginalized groups other than blacks (“You are you even before you.”; “Why do you feel okay saying this to me?”; As usual, you drive straight through the moment with the expected backing off of what was previously said.”). Furthermore, Rankine is aware that, in a Postmodern world, identity is fractured, though she advances a collective identity and meta-narrative based on Race. Hopefully, Rankine and Loffreda will expand this program and other writers will initiate their own. The project under review makes clear that poets need to talk among themselves about definitions, motivations, craft, and priorities and that poets of color should dialogue about the potential to ignore facts that do not fit particular narratives or metanarratives. Though I was annoyed, throughout this volume, by numerous editorial oversights, and I had the impression that the book was hastily assembled, The Racial Imaginary is recommended as a genuine attempt to initiate a conversation about Race and Racism, presented via a variety of viewpoints from a diverse group of contributors.

No comments:

Post a Comment